Nope, it's not a Tex-Mex dish of grilled meat served on a tortilla. It's a little-known folk instrument with origins in Slovakia. (Wikipedia article) The mother of one of my students sent me links to a local fujarist . In years of traveling the world and learning about local musical heritage and instruments, I have never "met" a fujara and thought you all might find this interesting. Bob Rychlik lives in Maryland but has a fascinating life story (see 3rd link to learn more). http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Y5fonktBzQ http://www.overtone.cc/profile/BobRychlik http://www.ncsml.org/Oral-History/Washington-DC/20110808/136/Rychlik-Bohuslav.aspx There's even an international festival: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bhr6Tzo_n_8

3 Comments

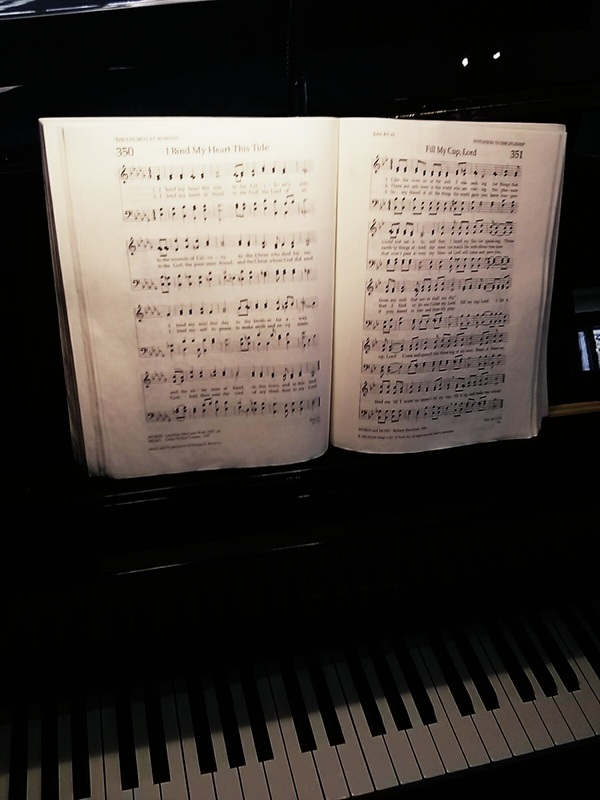

I was called in to substitute the music director at a local church this morning. My responsibilities included leading the congregation in the hymns throughout the service, and playing music for the prelude, meditation, offertory, communion, and postlude. I dug out some beautiful selections that I thought would be appropriate (shout out to my students Taura and Lukas: I included Valse Melancholique and Prelude from Espana) and arrived early enough to get settled, tag the pages in the hymnal, play through the hymns (once each), and circle the spots in the program that I would be playing. The first service went well.* While playing I thought that this experience would make a great topic to share and demonstrate how many of the skills we develop in lessons are important for situations in which we have limited time to learn new music. A few reminders:

After the conclusion of the service a member of the congregation came over to speak with me, and we quickly lost track of time. Soon, it was 10:45; time to get ready for the 11:00 service. I grabbed a bulletin from the front of the church and let out a little gasp. The hymns for this service were all different than the first service. I would barely have time to tag them, and absolutely no time to play through them. I began the prelude while concocting a plan. As the pastor led the church in prayer between hymns, I would look at the next selection and create a mental map of the hymn. This exercised another, very important skill for pianists:

The final selection was a hymn in D-flat major (5 flats). Oh joy... I appreciated all the folks after both services who came over to tell me how much they loved my performance. I resisted the urge to explain what a relief it was that things went well, but instead made an effort to thank them for having me today and wished them a lovely rest of their weekend. :) *Funny moment: an alarm on my phone (one that I didn't even know that I have!) went off at 8:59am, just as I was finishing the prelude. I finished the piece then dove into my bag to turn it off. I am sure my face turned a nice shade of pink. Many of my students know about my handstand quest: for a reason I don't quite understand, I so desperately want to be able to do an "effortless" handstand. To hop or kick or lift up into a handstand in the middle of a room (or better yet: my front lawn) and hold it as long as I like, before gently lowering down. And so, I've been practicing. A lot. Natalie (my roommate) teases me as my feet bump against the wall, morning and night. I read up on articles on what muscles I have to strengthen and various techniques of practicing handstands. And, slowly (soooo soooo slowwwwwly) I am getting there. I'm not entirely sure where, but I'm getting somewhere.

A few weeks ago I had a revelation. I realized that handstand practice is like piano practice, not only in the dedication it takes, but also how we feel when we are "safe" (practicing) versus "exposed" (performing).

Occasionally in yoga class, the instructor will catch me as I'm hopping up and assist me in my efforts. This is tremendously encouraging and exciting, as it seems like I'm closer to my goal. I do remember one class in which the instructor was passing by just as I was jumping up, and I expected that he would catch me. He kept walking. I fell. I laughed, nervously, and followed the class into the next posture. Later in class, he said: we have to be willing to fall, to feel the ground, to take the risk, to know that even if someone doesn't catch us, we will be okay... and that we grow and strengthen from this process.  Take a quick peak at the photo on the left. This is the piano that advanced young pianists used at today's NFMC Junior Festival at UMBC. Notice anything odd? Look under the music stand, in the corner closest to the camera. See it now? The white and green... toothbrush????!!! Yep - that's a real toothbrush that was found by one of the festival participants (there was a pencil right by it, too). Though the toothbrush didn't impact the sound of the piano (it would be an interesting prepared piano effect if it were on the strings) it did serve as a good indicator that this instrument is not particularly well-loved. [Sometimes I want to start a new organization: The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Pianos] Indeed, students were challenged by this beast of an instrument: from the bass notes not sustaining with the damper or sostenuto pedals, to the una chorda pedal creating intense dissonances and rattles, to an uneven sound quality across the keyboard. Yikes. A problem piano? Definitely. A fluke? Maybe (the recital hall piano was unexpectedly locked... and no one could be reached to come open it). A day in the life of a pianist? Yep. Unlike other musicians, pianists don't get to take their own (or their teacher's) instruments with them for performances. That means we at the mercy of whatever is provided (don't remind me about the times that the concert organizers "didn't realize" I need a piano, or time the TV producer assured me that I can play without pedals for a televised performance with orchestra). Sometimes we luck out and get a beautiful instrument that is easy to play. Other times, we have to work MUCH harder to create an effective performance. Do we give up when we get a piano that isn't up to our normal standards? No! I liken our challenge to the process of a chemist analyzing a water sample: we must evaluate the instrument's strengths and weaknesses quickly (sometimes instantaneously, if we don't have a chance to try out the instrument before diving into the performance) and create a plan of action to make it sound as best as it possibly can. I have witnessed many a fine pianist turn a "bad" piano into a beautifully singing instrument through their expert voicing, determined expression, and careful avoidance of the piano's weaknesses. Thus, I believe whole-heartedly that it can be done. It's not easy... but we need to be ready to step it up a notch when the time calls for it. This challenge can be:

Dr. Stephanie Bruning said that "flexibility is a good middle name for a pianist." I agree! The audience has sympathy for the plight of the performer, however in the end, all they want is a beautiful performance, and it's your job to make it happen. Congrats to all 29 Piano Prodigies students who performed at today's National Federation of Music Clubs Junior Festival at UMBC. The hard work paid off! Beautiful performances.

Great article, featuring my sister's beloved professor at Peabody, cellist Amit Peled.

http://peabodyinstitute.wordpress.com/magazine/vol-8-no-2-spring-2014/the-nature-of-nurture/ “So, how did it go?” Peled queries a student about a recent performance in New York. The student hesitates for a moment and responds, “Well, it was good. My biggest problem is that I get nervous.” Peled waves his hand dismissively. “Look,” he says, “everyone has that fear. You must overcome it. Everyone must. It’s not like practicing at home. The stage is totally different. You must prepare for it. You don’t just go out there. It’s very personal what people do before a concert. But right before you go onstage, you should just play and play and play. Be completely warmed up. That’s what athletes do. They pump up the muscles before a game.” At the end of their hour together, the student places his cello and bow back into a case and informs Peled that he plans to enter a prestigious competition and will try to win. Peled shakes his head. “You don’t want to try. You want to win,” he says. “That’s the right attitude. Don’t do competitions as an exercise or experiment or just to play. That’s a waste of time. You want to win!” In my last post, I went over the benefits of regular scale practice (and the resulting mastery of all 24 scales). Here are some ways to practice scales (and make them just a bit more fun):

Direction: 1. THE BASIC: 1-2 octaves (young beginners) or 4 octaves (intermediate and advanced) in parallel motion. Hands move in the same direction at all times. 2. CONTRARY MOTION: Both hands start on the same key (e.g. for C major, both hands on middle C) and move in opposite directions. The notes will not be the same but (for most scales) the fingering will be the same. Two octaves each direction. 3. RUSSIAN SPLITS (late intermediate): Two octaves parallel ascending (start low), two octaves contrary and back, two more octaves parallel ascending, two octaves parallel descending, two octaves contrary and back, and two more octaves descending (to get to starting position). 4. TRIPLETS (advanced): LH plays a one-octave scale low in the keyboard. RH starts an octave above and plays triplets (3 notes per LH note) for four octaves. Continue this pattern until the hands return to the starting position (it will take ___ complete RH scales to get to this point). Then switch: RH plays a descending one octave scale at the top of the piano, LH plays a descending four octave scale in triplets. Articulation and Dynamics: 5. All legato. 6. All staccato. 7. Legato on the way up, staccato on the way down (and reverse) 8. One hand legato, the other hand staccato. Try for the entire scale, or switch halfway. Or switch every octave! 9. All forte. 10. All piano. 11. Forte on the way up, piano on the way down (and reverse) 12. Crescendo on the way up, diminuendo on the way down (and reverse). 13. Crescendo to the halfway point of the ascent, then diminuendo to the top. Same on the way down (and then reverse). 14. One hand forte, the other hand piano. Try for the entire scale, or switch halfway. Or switch every octave! Variations: 15. THIRDS: LH starts on the tonic, RH starts a 3rd above (median) 16. SIXTHS: LH starts on the 3rd note of the scale (median), RH starts a 6th above (tonic) 17. TENTHS: Like thirds, but with an octave in between 18. OCTAVES. Both hands playing octaves. Some helpful links: http://www.true-piano-lessons.com/piano-scales.html http://www.pianocareer.com/piano-technique/piano-scales-arpeggios-art-exercise/ http://kantsmusictuition.blogspot.com/2007/09/method-of-practising-scales.html Not many students would call practicing scales fun (at least, until they become fluent in them). When I ask students why we practice scales, broken chords, cadences, etc. I usually get a blank stare, unhappy face, and a response that goes something like this: "Because... we have to?"

Scales are an essential skill for every musician. They develop:

Performance psychology is a very interesting field and important topic for performers of all sorts (musicians, athletes, public speakers, etc). There are many approaches to building and maintaining confidence under pressure. Here are a few of my thoughts on preparing for a successful performance:

|

AboutElizabeth Borowsky is a pianist, teacher, and composer. She is a Nationally Certified Teacher of Music in Piano (Music Teachers National Association). SubscribeCategories

All

Archives

May 2023

|

Location |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed